Curatorial programmes (the first of which, the École de Magasin, was established in 1987) attract a lot of scepticism from within the art field for what I think are three main reasons. The first is the idea that you can’t ‘teach’ curating. This is a view inherited from curatorial work in its more traditional sense, which is primarily concerned with the conservation and administration of objects in a museum context, and carries over to the more recent emergence of the superstar independent curator, such as Hans Ulrich Obrist and Nicolas Bourriaud, who typically finds their way to curatorial work through a background in art history, philosophy or art criticism. Here, the curator is viewed as a self-starter, in which specialised forms of knowledge are applied, in a unique and idiosyncratic way, to an individual cultural practice. Secondly, such programmes, appearing concurrent to the increasing prevalence of the independent curator in the late 1980s and early 1990s, represent a massive expansion of the scale and cultural reach of the art world and a corresponding opening up of professional opportunities.1 In light of the much discussed professionalisation of the art world, Curatorial Studies is often seen as an unnecessary disciplinarisation of what is inherently an unwieldy field of cultural practice, and one that serves largely to legitimise the positions of those practitioners who are already comfortably established in an institutional setting.2 Finally, as they are often highly expensive and offer training in a field that twenty-five years ago didn’t exist in an academic setting, many have the sense that these programmes provide a shortcut to accessing a highly competitive job market that, while always elitist, perhaps used to have a greater claim to meritocracy than it now does.

Having graduated from one of these programmes, the Center for Curatorial Studies (CCS) at Bard College, New York, earlier this year, I would suggest that while much of this scepticism is well-founded, at issue is not so much whether curating can or should be taught, but whether the position of the curator that these programs ostensibly train for remains a viable one. My intention here is not to dispel the validity or worth of such programmes, but to argue that they emerge from a highly specific historical situation that is increasingly untenable. Although the hyper-professionalisation that spawned these programmes remains very much in force, recent structural shifts in the contemporary art field have arguably stretched curatorial discourse to the limits of its plausibility. In particular, the role of contemporary art in the financialisation of the global economy, as well as the explosive effect of social media on image culture and circulation, challenge claims to curatorial work being a specialised form of knowledge, along with the central role of the curator in the discourse of the art world. In order to explain with greater particularity what I take these claims to be, I wish to summarise an influential account of the discipline by the current director of the graduate programme at CCS Bard, Paul O’Neill, and relate these to recent developments in contemporary art as well my own experiences navigating the New York art world.

O’Neill’s book The Culture of Curating and the Curating of Culture(s) traces the historical emergence of the independent curator, claiming that the curator has become an auteur-like figure on par with artists. There has been a shift, he argues, from curating as a caring, meditative and fundamentally administrative activity, to a mediating, performative one, in which the curator now occupies a centralised, highly visible position within the art world. This ‘curator-as-artist’ figure is one that, for O’Neill, emerges alongside artistic practices (paradigmatically, relational aesthetics) that increasingly incorporate administrative and collaborative dimensions, thus undermining the autonomy of art that would hold artistic practice and its supporting functions apart from one another. Central to O’Neill’s account of this confluence between the curator and the artist is the view that the temporary exhibition is the ‘mediating event through which art discourses are produced and transformed’.3 But it is worth asking whether, in an era where artwork is perhaps primarily seen and distributed online, and the artist an increasingly branded persona mediated through social media, the exhibition form retains the same primacy that it had in the heyday of the biennale and international group exhibition.

For example, we might point to websites such as Contemporary Art Daily or Art Viewer, where although the exhibition remains the primary organisational structure, the installation images they display have been largely divorced from their original institutional context, and are subordinated to the website’s own aggregatory logic. Art historian Michael Sanchez wrote about this in a 2013 article for Artforum, in which he suggested that Contemporary Art Daily has dramatically altered the rhythm of the art world from the seasonal cycles of the exhibition, the fair and the biennial to one that is now instantaneous.4 Such websites also potentially unmoor the circulation of art from the traditional gatekeepers of galleries, critics, institutions and, of course, curators, by allowing for the free and limitless distribution of the art image on social media.

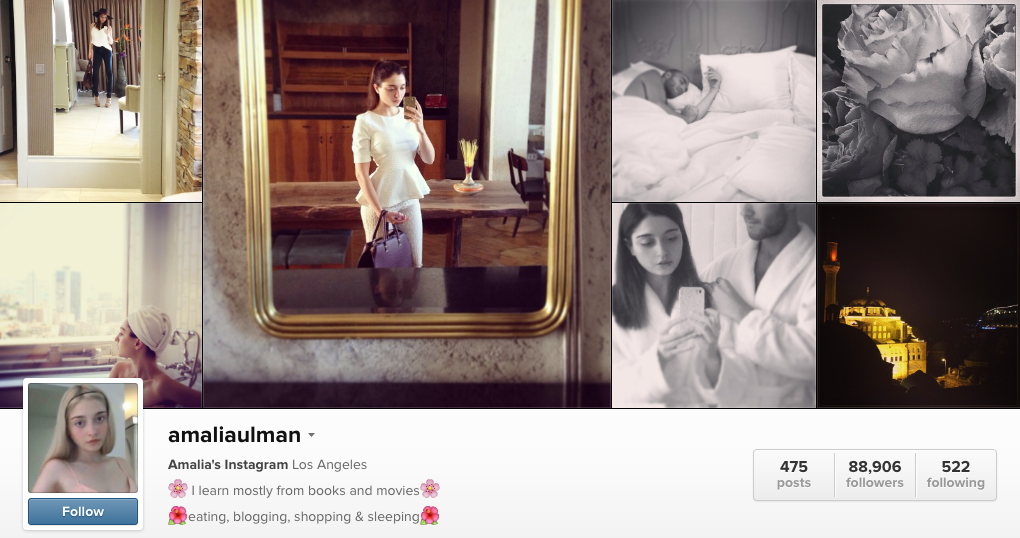

Amalia Ulman, Excellences & Perfections, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

Another effect of recent technological shifts and the ubiquity of social media is the way in which artists can increasingly take control of the distribution of their work. These developments find artists administering their own self-image and public persona in a manner not unlike that of a brand, a phenomenon perhaps best illustrated by those artists who maintain an active social media presence that promotes, and in some cases becomes part of, their practice. In an article examining self-portraiture in the digital age, New Museum curator Lauren Cornell discussed recent practices in which social media often forms an integral part. Amalia Ulman’s Excellences and Perfections project—a semi-fictionalised performance on Ulman’s personal Instagram account in which the artist has breast augmentation surgery, adopts the Zao Dha Diet and takes pole-dancing lessons—was only revealed as an artwork when the artist made a public announcement that the previous months of social media activity had been a now concluded performance. In other words, artistic practice has become indistinguishable from persona. As Cornell notes, ‘it’s unclear how Ulman’s audience sees her: it’s likely some of her followers see the work as performance while others see it as the true story of a relatable blonde in search of the perfect "after" shot to the extreme makeover process’.5 Ulman’s project is but one notable example of recent shifts in artistic practice away from the exhibition as its primary contextual marker, towards a deeper imbrication in the microcelebrity logic of social media.

While this results in a hybrid figure not unlike the artist-curator/curator-artist described by O’Neill, in which Ulman simultaneously occupies the roles of artist, social administrator and brand ambassador, the social context in which her work exists is very different from the institutional and collaborative one that is so integral to these earlier formulations of the curatorial. For O’Neill, the curatorial is fundamentally dialogical and prompts a rethinking of the concept of aesthetic autonomy. Instead of grounding artistic practice in notions of individual autonomy and subjective exceptionalism, the curatorial instead proposes ‘an understanding of autonomy as a sensibility toward the continued production of exchanges, commonalities, and collective transformations, beyond any prefixed ideas of profession, field of specialisation, or skill set’.6

This is a particular critique of artistic autonomy that emerges in the late 1980s and early 1990s alongside the so-called ‘social turn’, and which art historian Lane Relyea, in his excellent book Your Everyday Art World, argues is tied to broader shifts occurring in and around the art world at this time; namely, ‘a rise to dominance of network structures and behaviors and their enabling manifestations’.7 However, Relyea also reminds us that this network paradigm, for which the dialogical/relational, flexibility and mobility/nomadism are defining concepts, is deeply intertwined with the political, economic, cultural and social shifts typically associated with neoliberalism.8 Moreover, the decidedly utopian terms in which ‘the social turn’ in artistic and curatorial practice are often described, actively obscures the ways in which the social is now the key generator of value in what sociologists Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello have called ‘the new spirit of capitalism’.9 And indeed, it’s difficult not to hear in O’Neill's description of the curatorial echoes of a now ubiquitous Silicon Valley rhetoric of collaboration, flexibility and the like.10

Rather than facilitating dialogical exchange, artistic practice is reconceived in Ulman’s Excellences and Perfections as participation in a social field that is structured around attention. Recent moves towards the participation of art in an expanded field of image flows have predictably incited the disapproval of critics who have been invested in contemporary art’s ‘social turn’, before the social became synonymous with social media. One need only look at the barrage of negative reviews of this year’s Berlin Biennale (curated by online publishers DIS)—like Jason Farago’s claim in The Guardian that DIS’s failure to consider current events such as Europe’s refugee crisis is ‘a puerile misunderstanding of what art is and what it can do’—as evidence of this.11 A more nuanced, although no less reactionary, take on art’s increasing incorporation with contemporary conditions of image circulation can be found in Claire Bishop’s remarkably pithy review of Danh Vo’s participation in last year’s Venice Biennale. Lamenting the lack of historical depth in the exhibition the artist curated at the François Pinault Foundation’s Punta della Dogana, Bishop derides the tendency for artist-curated shows to function as displays of individual artistic sensibility at the expense of interpretive rigor, concluding, ‘and who needs artists for this job, when such pleasures exist all over Instagram?’12 What both critiques share is a liberal lament for the exhibition as an autonomous space of free exchange and open-ended collaboration, untainted by the narcissistic impulse of self-promotion, or the desire, presumably, to have a career. Work such as Ulman’s—or for that matter DIS—recognises that the site of artistic practice has long since shifted to the social field at large from the institution, a context to which many of the architects of the social turn paradoxically remain beholden.

But the role of the curatorial in an art context that increasingly eschews institutional framing is far from clear. If the 1990s witnessed the dissolution of traditional notions of art’s autonomy in favour of its integration with the systems that produce it, then more recent years have seen this condition taken so much for granted that it would appear to be forgotten. Take the situation in New York currently, where the art scene feels like a well-oiled feedback loop—the city is saturated with younger artists and galleries vying for entry to the market, blue-chip artists are getting more critical and institutional attention than ever and museums seem content with scooping up the most well-connected artists from both sectors. With social media ensuring this loop extends the globe, its allure of democratisation obscures the extent to which these new mechanisms of visibility rely on very old hierarchies. Self-awareness of our networked condition may be at an all time high, but an awareness of the shape of these networks, and their power, remains vague at best.

Perhaps what is needed then are less overinflated claims about the importance of curatorial labour, and more attention being paid to how this labour actually functions within a highly networked social ecology that often appears formless or organic but is in fact highly fractious. In an essay published last year called ‘The Outside Can’t Go Outside’, artist Merlin Carpenter recapitulated a by-now standard refrain: any attempt to position art in opposition to or outside of systems of capital accumulation is doomed to failure and will be immediately reincorporated towards exactly that.13 DIS (whom he terms ‘self-curators’) comes under particular fire in that their efforts to render the distinction between the art system and related cultural and economic systems void, serves only to further exacerbate the totalising effects of what he calls ‘authoritarian capitalism’.14 The mistake of such contemporary, pseudo-critical art practices, according to Carpenter, is to presume that an awareness of the art world as a system for the production and circulation of value is itself a critical gesture. If the critical potential of art has recently been thought to lie in its ability to represent systems (i.e. to draw connections between disparate objects), Carpenter suggests quite the opposite; that art might be valuable for its ability to divide things into groups:

From group formation as action you can work out the connections between actors in neighbouring groups, locating parallel struggles – maps of common groups, maps of types of groups – or groups that imply another kind of group, whether legitimised or not, and form meta groups against control networks, in a re-ordering of class struggle.15

Rather than a systemic critique of the art world and its corresponding strategies of experimenting with alternative divisions of labour, equalising representation and avoiding commodification, politically effective action might instead consist in antagonism, nepotism and a fundamentally antisocial and anti-relational approach.

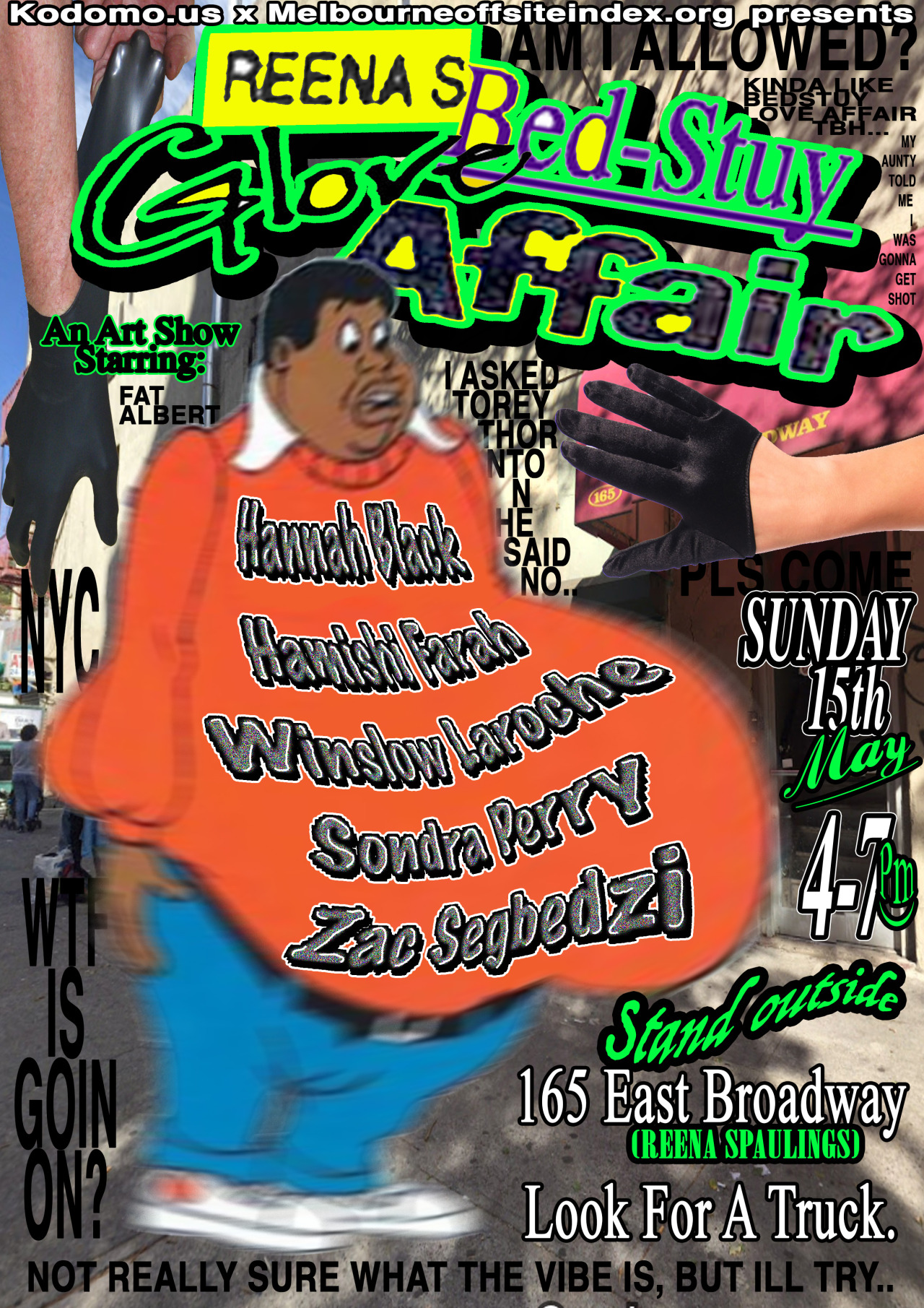

Zac Segbedzi, event poster for Reena's Bedstuy Glove Affair, Reena Spaulings, New York, 15 May 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

One example of what this might look like is Reena’s Bedstuy Glove Affair, a pop-up exhibition organised by Melbourne artist Zac Segbedzi earlier this year. The exhibition’s title refers to two notoriously hip New York galleries, Reena Spaulings and Bed-Stuy Love Affair, and featured work by five black artists: Hannah Black, Hamishi Farah, Winslow Laroche, Sondra Perry and Segbedzi himself. Situated in a truck that was parked on the street outside of Reena Spaulings, and organised during an ill-fated trip taken by Segbedzi and Farah (who was detained at the airport and not allowed into the United States) to New York to participate in the NADA (New Art Dealers Alliance) art fair, the exhibition was a fairly direct provocation towards the subcultural status of two galleries that wield an enormous amount of social and cultural power. Moreover, Segbedzi’s position here as a dual outsider (i.e. a black Australian) suggests that these spaces are complicit in the systemic exclusion of certain individuals from art world institutions on the basis of factors such as race and citizenship. Yet the urgency of Reena’s Bedstuy Glove Affair is due to the pointed specificity of its critique, which taking the form of an ‘us against them’ mentality enables a broader critique of the exclusionary mechanisms that shape the art world.

Missing from many of the less critical accounts of curating’s new spirit is the recognition that dialogue, exchange and collectivity take place on an uneven social field—one that is particularly distorted by the tightly-knit social and institutional networks that characterise the art world. Another of my professors at CCS Bard, Suhail Malik, provides a refreshing counterpoint to much of this discourse in his analysis of the art world. In an essay written for the 13th Istanbul Biennial in 2013, Malik argues that there is a deep ‘structural and political congruence’ between contemporary art and ‘the national and global re-organisations of wealth and power over the last twenty years or so in favor of elite wealth’.16 He suggests that not only is the social and economic organisation of the art world fundamentally shaped by this reorganisation, but that, owing to its cartel-like social structure, ‘contemporary art is a key mechanism in the cultural legitimation of that process’.17 Malik cites three characteristics of the art world that define it as a cartel: its transactions are informal and unaccountable, and are made on the basis of personal preference without any regulation or clear criteria; the primary and secondary markets are intertwined and capable of manipulating one another; and despite art being an ostensibly public good, all significant decisions are made behind the scenes, in private and accessible only to insiders. This cartelisation—and its concomitant notion that there is something inherently virtuous, and thus worthy of special protection, about art—is what enables ‘the concentration of cultural and artistic power’ to be repackaged as a civic virtue through the public exhibition sector.18

Anonymous meme, 2015.

Clearly, such a perspective on the art world calls for an understanding of the role of the curator that is radically different from that of the benevolent dialogical actor posited by O’Neill. What is clear from Malik’s account is that there is a danger to regarding social relationality as ipso facto a good thing when the art world’s cartel-like structure not only ensures that its participants skew disproportionately to the culturally and financially powerful, but in fact actively works to concentrate that power. Malik’s critique thus allows for what I think is a more accurate and responsible understanding of curatorial work as fundamentally imbricated in the networks of wealth and power that aren’t so much a necessary evil as they are the structural basis of the art world.

To return to questions raised at the start of this essay on the viability of the curator today, the diminishing importance of the exhibition as the primary mechanism through which value is allocated to artistic practice has gone hand in hand with the mediating function of the curatorial becoming widely accessible to artists, other cultural practitioners or anyone with a social media account. Similarly, the connective, networking function so enthusiastically advocated by much curatorial discourse has with historical distance revealed itself as an alibi to the neoliberal impetus that makes deeply hierarchical relationships appear flat. The dilemma for the curator, or really anyone working in the art world, is how, if one is committed to a politically progressive politics, to avoid simply facilitating what the entire mechanism of value creation in the art world is set up to do: consolidate the wealth of the already very wealthy. I don’t think there’s an easy answer to this, but my sense is that understanding curatorial labour as primarily occupying a mediating role—networking, facilitating collaboration, connecting artists with institutions and vice-versa—overlooks the extent to which this role is also one of being a gatekeeper to limited resources, whether that be visibility, institutional validation or capital. Rather than treating art as an inherent social good and the curator as a benevolent actor, it’s important to recognise that curatorial decisions are an allocation of cultural value that often has a direct economic effect on the parties involved. The image of the jet-setting independent curator is a fantasy that belies the socially aspirational aims of the social turn.